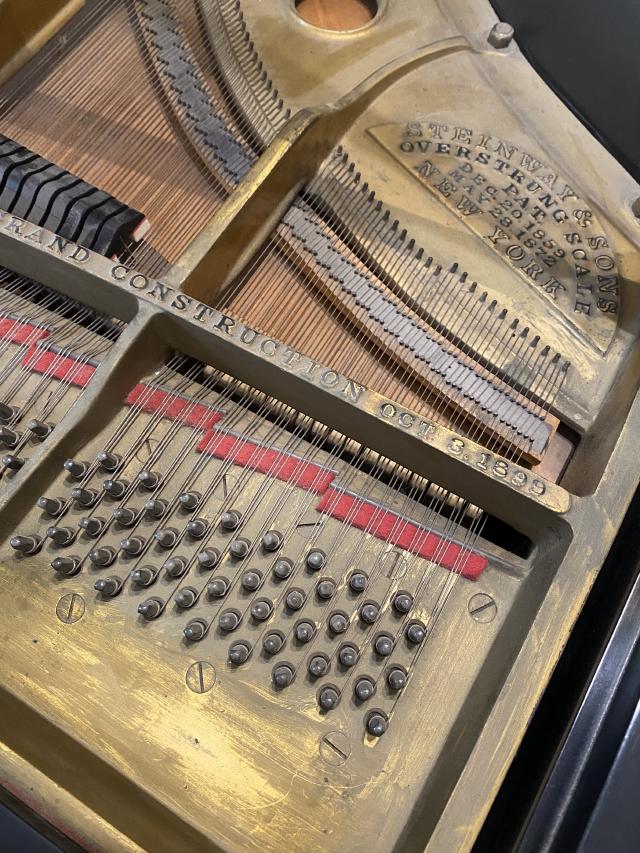

I found this Steinway on an estate auction website. It was in New Jersey, not particularly close or convenient, but it was an opportunity. As with most estate auctions, there was practically no information about it aside from dimensions. The plan was to factor in the price of a full rebuild, a process which is labor intensive, expensive and generally only financially worthwhile on a premium brand piano that would fetch a decent resale value (otherwise a new piano would be cheaper). I knew that Steinway “shells” (the solid core of a piano to be rebuilt) are worth around $4k, and that’s what I managed to get this Steinway for.

I guessed from the dimensions that it was a Steinway Model O (5’ 10¾" in length), and an old one based on the keylid decal and decorative music stand and case. Thankfully I didn’t need to trek out to Jersey and waited for the movers to bring it to NYC. When it arrived and the movers squeezed it in next to the Kawai, I realized I was right to expect a full rebuild. It was dirty, dusty, well and truly worn and not particularly functional.

Along with the piano I received a leather shoulder bag full of random sheet music, notes and even paperwork from the purchase of the piano. It seems this owner had bought it in California in the 1990s. Although the serial number of the piano identified it as being built in 1905 (nearly 120 years old - around the time of the first flight, and well before the Titanic sank), it was probably at least partially rebuilt in ’90s. The keytops would have originally been ivory, they were now plastic, and a few of them detatching.

I spoke to a handful of piano rebuilders in the area and received their proposals. One of the big questions in a restoration like this is whether the soundboard would be replaced. There are many different opinions about this, ranging from “always replace a soundboard of this age” to “keep the soundboard and just repair it as often as possible”. Some believe the quality of wood used at this time was slower growing, and therefore had a tighter grain leading to a better sound. Other differences of opinion were regarding whether other parts of the piano should be replaced or repaired, and which brand of parts should be used. I ended up choosing a rebuilder who invited me to his workshop where I could see the work he and his team were doing, and play many pianos he’d already built. Another big decision of the rebuilding process is which type of hammer to install. The felt and construction varies between brands and can substantially change the tone of the piano. While at the workshop I was able to play a number of pianos with different hammers (New York Steinway, Renner, Abel), as well as some with new soundboards and some with repaired soundboards.

I decided to focus on only the interior and mechanics of the piano with only minor aesthetic repairs (nickel-plating the blemished hardware and pedals, polishing the existing finish and putting on a new Steinway decal). Stripping back the wood and applying a new finish would have to wait for another time. Soon the piano was packed up again by the movers and the work began. Once it was disassembled, the rebuilder thought it was best to replace the soundboard. The original soundboard had flattened it was decided the best result would be a new board.

One of the more curious repairs the piano needed was a thickening of the keys. Whether by design, or by wear, the keys on the piano were slightly thinner and had noticable gaps between the keys. The rebuilder shimmed all of the keys with veneer on the sides to add width, and the new keytops were shaped to match. It makes a massive difference, and didn’t require the entire keyboard (which was otherwise fine) to be rebuilt.

In the end the total cost of the piano and its rebuild came to about 20% of the cost of a new Model O from Steinway and about 40 to 50% of the cost of a rebuild model from a showroom.

When you see how much of the piano is replaced in a large scale rebuild like this, the Theseus’ ship comes to mind. Even though the hammers are Steinway parts, other components come from other manufacturers and it becomes something else, or so Steinway’s sales department insists. Even so, it has a whole new life now, a new sound, and is ready to begin its next 120 years.